By Doresa Banning

In the 1940s and 1950s, Nevada appeared to be harboring fugitives, individuals whom other states wanted to prosecute for allegedly violating their anti-gambling laws. Nevada bore “the stigma of being a refuge for fugitives trying to avoid extradition,” said state Assemblyman Roger Bissett in 1961, as reported by the Reno Evening Gazette on March 24. Two high-profile cases especially tainted the Silver State this way.

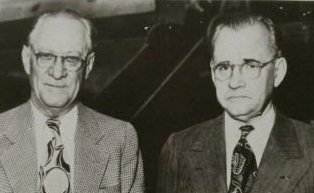

Lincoln Fitzgerald, Danny Sullivan

In fall 1946, Nevada Governor Vail Pittman received an extradition warrant from Michigan for the arrest and return of Lincoln Fitzgerald (age 50), Danny Sullivan (56), and Mert Wertheimer (62). At the time, the three had been running the Nevada Club and residing in Reno for about eighteen months.

Danny Sullivan (left) and Lincoln Fitzgerald, 1949

A Macomb County grand jury had indicted them on two counts of conspiracy to violate gambling laws and one count of obstruction of justice through bribery. The trio allegedly had run a gambling syndicate there between August 1940 and July 1946 — “keeping and maintaining for hire and reward gaming rooms, gaming tables and devices, and games of chance” in several locations — and had paid the district attorney, assistant D.A., and two state police officers to allow their operations to continue unfettered, the Nevada State Journal reported on November 8, 1946.

Wertheimer immediately surrendered and returned to Michigan where he was acquitted and fined $6,500 (about $80,000 today when calculated for inflation). Later in 1949, he would run the casino at Reno’s Riverside hotel and subsequently co-own the entire property.

Mert Wertheimer

Unlike Wertheimer, Fitzgerald and Sullivan, who were arrested and released on $1,000 bond each in Reno, fought extradition via their attorneys, William Cashill and Douglas Busey.

At the time, Nevada followed the extradition laws outlined in the U.S. Constitution, Article IV, Section 2 and the U.S. Code, Title 18, Section 3182. Unlike Nevada, by 1946, most other states had adopted their own version of the Uniform Criminal Extradition Act, a simplified set of procedures for interstate extradition.

For an extradition request to be valid, according to the constitutional and statutory provisions under which Nevada abided, it had to: (1) be in writing, (2) charge the accused with the commission of a crime under the demanding state’s laws, (3) allege the accused was present in the demanding state when the alleged crime was committed, (4) allege the accused fled the state after that time, and (5) have with it a copy of an indictment or a supporting affidavit.

Against the advice of Nevada Attorney General Alan Bible, Pittman refused to sign the extradition warrant because he believed a one-man grand jury like Macomb County’s was unconstitutional and unfair. Bible argued that Michigan’s legal procedures were irrelevant as long as the demand documents were proper.

Macomb County responded by having a twenty-man grand jury re-investigate possible crimes by Fitzgerald and Sullivan. It found what the previous legal body had, which led to a second request for the duo’s extradition. In March 1947, they again were arrested, this time in the rural Nevada town of Ely, and freed on $1,000 bail apiece.

Pittman sanctioned the extradition. Cashill and Busey immediately filed for a writ of habeas corpus, the typical move to effect a hearing for review of the legality of an arrest, detention, or imprisonment.

With respect to such a writ, per the U.S. Constitution and Code, the court may only determine whether or not: (1) the demanding state charged the petitioner with a crime, (2) the petitioner was in the demanding state when the alleged crime occurred, and (3) the petitioner is a fugitive from justice.

At the mid-July writ proceedings, attorneys from the Ely law firm of Gray and Horton, on behalf of the wanted men, argued that the indictment was defective under Michigan laws and that the indicting jury had been empaneled defectively. They also asserted, because Fitzgerald and Sullivan had been in Nevada for more than a year prior to the first indictment, that their business would deteriorate were they returned to Michigan.

Bible countered that the writ should be denied, emphasizing that the legality of Michigan’s grand jury wasn’t Nevada’s province to decide.

Ely District Judge Harry Watson denied the writ because the empaneling procedure hadn’t been sufficiently irregular to justify granting it. On appeal, the Nevada Supreme Court in August affirmed Watson’s ruling.

The defense attorneys then filed a petition in district court for a re-hearing of the habeas corpus writ based on new evidence. They purported three of the Michigan grand jury members hadn’t taken the requisite oath of office before indicting Fitzgerald and Sullivan and the county clerk fraudulently had inserted into the records proof of the oath after the fact.

Watson allowed a re-hearing because the indictment, worded exactly as the first, failed to represent a new and independent effort. “All Michigan authorities have to do if they want Fitzgerald and Sullivan returned,” he added, “is to follow the proper legal procedure in indicting them,” the Nevada State Journal noted on October 1, 1947.

Bible, however appealed to the higher court. A court date was scheduled for February 1948.

Also, taking a cue from the defense’s playbook, Bible, along with White Pine County District Attorney C.J. McFadden, petitioned in October in district court for a re-hearing on the writ on grounds that Judge Watson’s granting of the writ was against the law, that the evidence presented in court regarding Michigan grand jury procedure was irrelevant, and that Nevada courts had no jurisdiction over Michigan grand jury procedure.

Before that filing could be addressed, though, Michigan sent its third request for Fitzgerald and Sullivan’s extradition, this time a justice court warrant in the form of a certified complaint by Governor Kim Sigler.

Again, Pittman signed off on it, and Fitzgerald and Sullivan were processed in and out of jail.

A habeas corpus writ hearing was held, at which Bible reiterated his previous points. Cashill contended that the extradition demand should be dismissed because: (1) it was a continuation of two earlier requests, (2) it constituted persecution for political purposes by certain Michiganites, (3) it was suspicious that the extradition demand came seven years after of the alleged crimes, (4) the filer of the affidavit (the governor) lacked knowledge of the alleged crimes, and (5) Fitzgerald and Sullivan’s constitutional rights were being denied.

In January 1948, District Judge William Hatton of Tonopah, another rural Nevada town, sat in for Watson at Bible’s formal request because of perceived bias due to his involvement in the previous hearings. Hatton also disallowed the writ. He stated that the affidavit contained sufficient evidence to warrant extradition and that Fitzgerald and Sullivan were fugitives. He ordered that they be jailed without bail pending the upcoming Nevada Supreme Court’s review of the case.

The next month, in legal precedent, the higher court terminated the White Pine County appeal because, it opined, no right in Nevada exists to appeal the state supreme court in writ of habeas corpus cases. That is the case to ensure “the liberty of one unlawfully deprived [is] speedily restored to him and that such restoration [is] final,” reported the Nevada State Journal on February 3, 1948.

Due to complaints about Fitzgerald and Sullivan’s constitutional rights being denied, the matter also went federal. In February, Federal Judge Roger Foley ruled as Tonopah District Judge Hatton had, that Michigan’s affidavit was adequate, Fitzgerald and Sullivan were fugitives and the extradition documents met the legal requirements. He granted them each bail of $5,000.

Attorney Cashill appealed to the federal circuit court of appeals in San Francisco. Months passed while awaiting a court date.

In August, the Macomb County sheriff and new prosecutor secretly traveled to Reno, where their movements and dealings were kept secret.

A week later Fitzgerald and Sullivan surprisingly surrendered and were extradited.

Likely in an arrangement negotiated by Cashill, they pled guilty in a Michigan court to minor charges and received no jail time. The judge ordered Sullivan to pay a $700 fine and $33,000 (about $329,500 today) in costs and Fitzgerald, a $300 fine and $18,000 ($180,000 today) in costs. He also gave each of them one year’s probation but allowed them to leave Michigan at any time.

They returned to Reno and continued the lives that they’d established there two and a half years earlier.

Lester “Benny” Binion, 1979

Benny Binion

In January 1950, Lester B. “Benny” Binion (45), former Texas gambler, was a legal partner in the Las Vegas Club casino and had been living in Nevada for four years.

Dallas District Attorney William Wilson charged Binion with operating a policy wheel racket, or numbers game in Texas in 1949. Texas considered the activity — in which the player bets on three numbers that will be drawn randomly the next day — an illegal lottery and demanded the Silver State extradite Binion.

Binion’s attorney, Harry Claiborne, got a writ of habeas corpus from District Judge Frank McNamee in March by proving that the accused hadn’t been in Texas at the time of the alleged offense, thereby fending off extradition. (Conversely, under the UCEA, a person charged with a substantial crime can be extradited whether or not they were in the accusing state at the time of the crime.)

Wilson’s subsequent attempt to have Binion extradited — that time for the same crimes but on different dates of commission — also failed. In July, District Judge D.W. Priest found that Texas officials had failed to present any new evidence, and he granted Binion a habeas corpus writ.

Two and a quarter years later, in October 1952, a federal attorney requested that Nevada return Binion to Texas to face charges of income tax evasion. The Internal Revenue Service filed a tax lien against him, charging that he and his wife owed $862,500 in back taxes (about $7.7 million today). Binion, who by this time was the owner and operator of the Horsheshoe Club in Las Vegas, appealed.

In January 1953, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed his case for being frivolous. Similarly, three months later, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review it.

After additional unsuccessful appeals, Binion was extradited in September. He pled guilty to two tax evasion and four gambling counts. With concurrent sentences for federal and state charges, he served five years in the United States Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, between December 1953 and March 1957.

Ultimately, Binion had avoided extradition for nearly three and a half years and had reaped the benefits of operating Nevada casinos during much of that period.

Impact on Nevada

Many believed the Fitzgerald/Sullivan and Binion extradition cases marred the honest, clean reputation Nevada officials toiled to maintain, especially regarding its top industry, gambling. By allowing years to pass in which the gamblers remained free and operated profitable gaming establishments in Nevada, the state appeared not only to be protecting the gamblers from justice for their alleged crimes but, also, to be aiding them in circumventing other state’s laws. “The integrity and honesty of Nevada is at stake because of these continued delays in the carrying out of justice,” Bible said during the Fitzgerald and Sullivan case, as reported by the Nevada State Journal on October 1, 1947.

The Silver State drew criticism from Texas and Michigan, too. “In effect, it makes Nevada an asylum for racketeers,” Wilson said, referring to its stricter extradition laws, as noted in the Reno Evening Gazette on March 2, 1950. “Gamblers can now stay in Nevada and operate rackets in other states through agents and avoid prosecution.”

To prevent that very scenario, the Nevada Tax Commission, a division of which then oversaw gambling, initiated two policies in May 1951: first, effective July 1951, no Nevada bookmaker or sports pool could accept bets on horse races or other sporting events from any out-of-state person or source; second, as of January 1952, gambling licenses would be denied to any individual who owned or controlled gaming interests outside Nevada.

Why did Nevada stick with the older extradition law for so long? In part, due to its lax divorce requirements, legislators wanted to afford divorcées the ability to sue their ex-husbands here if they stopped paying alimony. For instance, a man ordered to provide alimony to his ex-wife could move from one UCEA state to another, say Ohio and Louisiana, stop paying alimony and get away with it. This is because under the UCEA he’d be extradited back to Ohio where the alimony order had been issued, but Ohio would lack jurisdiction to prosecute for the crime since he’d committed it in Louisiana.

On the other hand, if the ex-husband moved to and stopped paying alimony in Nevada, under its extradition laws, he’d be kept here, where the ex-wife then could pursue legal action against him.

“Some Nevada attorneys have expressed a desire for the legislature to make the uniform extradition law effective here, but others oppose it strongly, especially as it would apply to domestic cases,” reported the Reno Evening Gazette on February 22, 1950.

Despite the concerns about Nevada’s standing among its peers, it wasn’t until 1967 that legislators adopted the UCEA, which is detailed in Revised Statute 179. Nevada was the forty-seventh state to do so.